In 2017, when it was still under construction, my first and only glimpse of CSW bus stop in Jakarta resulted in my utter amazement. Who had dreamed up this scary construction? I wondered how many people would be brave or fit enough to walk up to a bus station soaring 24 meters high above ground level – I envisioned very few would make the effort.

As I saw it, the station’s giddy height, its slender design and rather feeble looking handrails and balustrades, combined with Jakarta’s soaring air pollution and daily temperatures of 30 degrees Celsius or higher, would discourage even the most ardent user and advocate of public transport: myself included. These immediate concerns turned out to be prescient; the CSW bus stop was never fully utilised for all the reasons I’d anticipated.

U-turn

After that initial view, I didn’t give the station much thought. That is, until a few weeks ago when Yogi Fajri, a friend from Semarang, out of the blue, sent me images from this station. After seeing Yogi’s pictures though, there are now two very good reasons for me to visit CSW bus stop next time I’m in Jakarta.

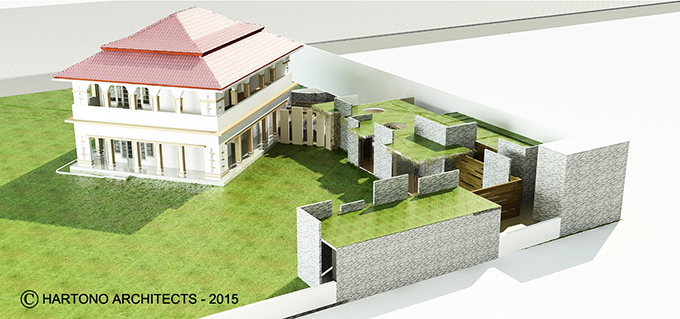

The first, is that the bus stop is no longer the scary platform floating somewhere in mid-air as it was when I initially encountered it. Instead, it’s an integrated part of CSW Asean Station, an impressive new public transport node in Jakarta’s rapidly expanding public transport network. Although the position of the platform hasn’t changed, the addition of two floors underneath and elevators connecting the different floors have considerably improved the platform’s accessibility and appearance, it’s no longer ‘scary’. For passengers who alight here, the raised and covered corridors at first floor level create easy, safe and fast connections to the metros and buses situated on second and ground level while shops, eateries, public toilets and a mosque on the newly added floors enhance the station’s user friendliness.

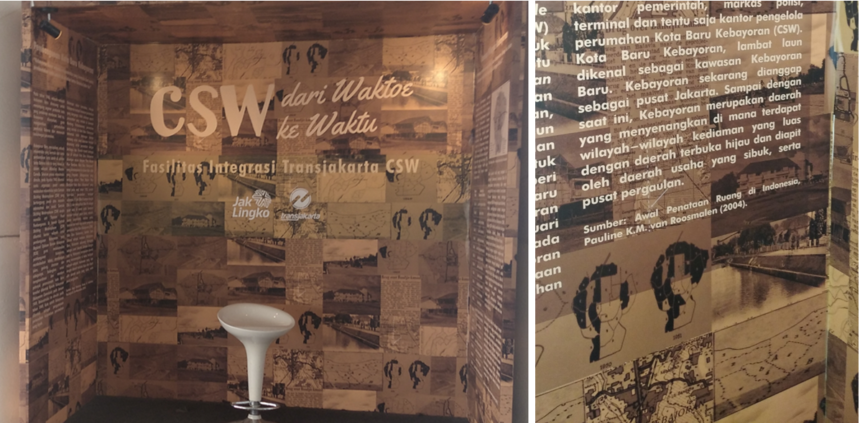

The second reason, and perhaps a more personal one, is a small booth in one of the transit spaces on the second floor that provides the station’s users with a brief history of Kebayoran Baru genesis and that of the area surrounding CSW Asean Station. Not because I’m curious to learn about the history of Kebayoran Baru, but because it would be fun to see, for myself, the reference to one of my own articles as the source of information for the story in the booth. For who would have thought that, my contribution to a rather obscure publication some two decades ago, would be cited as a source of information to inform passengers on Jakarta’s public transport.

An obscure publication

The book I’m referring to is called Sejarah Penataan Ruang Indonesia 1948-2000 (History of Indonesian Planning 1948-2000) and was the result of a joint initiative between the Indonesian Department of Settlement and Regional Infrastructure (Departemen Permukiman dan Prasarana Wilayah, KIMPRASWIL) and its Dutch counterpart. I contributed to the book thanks to an invitation by Steef Buys, the Dutch senior official who co-initiated this project. I was flattered by the invitation, not only because I recently started my PhD research at Delft University of Technology, but also because my co-authors were esteemed professionals and academics.

My chapter examined planning in the Dutch East Indies during the first half of the twentieth century. It discussed the myriad of issues planners dealt with, who these planners were, why and how they addressed the various issues, what plans they designed, and how colonial and early post-colonial planning in Indonesia were intrinsically connected. Considering the latter, my chapter was a good springboard to the following chapters dealing with the many aspects of planning in post-colonial Indonesia.

Unfortunately, the book’s anticipated readership of professionals, academics and university students never materialised. The reason was regrettable but simple: the limited edition of the book that was soft-launched in 2003 was never succeeded by a final version printed in large numbers. Although the book occasionally came up in conversations with colleagues and friends – including fleeting ideas to publish the book after all – it gradually turned into one of those books known to its authors, editorial team and to the people who attended its soft-launch, but few others.

Validation

I’m a firm believer in scholarly publications being shared in the public domain and wanted to avoid my chapter slipping into complete oblivion, I therefore uploaded it on various free to access online platforms. Whether the anonymous writer of the text in the booth at CSW Asean Station traced my text on any of these websites or managed to obtain one of the rare copies of the 2003 book, I don’t know. What I Do know is that somebody, somewhere, somehow, traced the text and used it to write a short narrative about the history of the area surrounding one of Jakarta’s public transport hubs. How’s that for delayed validation?!

Obviously, I’m fully aware that most passengers pass the booth without paying it too much attention. But as a Jakarta taxi driver once pointed out, even if only one percent of all passengers take notice, the impact is still considerably larger than if the information would have been confined to the pages of a somewhat obscure publication.